so, it's midterm week, and i definitely stayed up ALL NIGHT writing three papers, two of them being film reviews.

here's one of those labors of love now...

-stephanie

BEST IN SHOW (dir. Christopher Guest, 2000)

Christopher Guest’s film BEST IN SHOW (2000) delivers provocative caricatures of several different subcultures, inspiring critical reexamination of their follies, as any successful satire should. The film’s “mockumentary” style is particularly effective, as it allows the actors’ endearingly quirky exaggerations to be interpreted as near-truths. The artistic direction and photography mimic the aesthetic of film documentaries, making the audience feel that what they are seeing is merely a version of the truth. And indeed, it is. The film’s characters and situations are exaggerations, but these slightly hyperbolic depictions reveal underlying truths about the absurdity of human nature.

As the film tackles the conventions of professional dog shows, it highlights our assumptions and stereotypes of the people who participate in them. While we may initially laugh at the comedy and irony at the surface, deeper down, BEST IN SHOW works at exposing our assumptions and stereotypes of the crazed pet owner, and reveals a deeper understanding of the tragedy of middle-class America and a criticism of consumer culture.

Parker Posey and Michael Hitchcock evocatively portray the foibles of the yuppie subculture in their roles as contestants Meg and Hamilton Swan, respectively. We are first introduced to the Swans in the middle of what appears to be a family therapy session, where the Swans are discussing what we assume to be their misbehaving child. However, as the camera angle slowly changes to reveal, we are witnessing a puppy therapy session, and the patient, the focus of the characters’ (as well as our own) attention is actually the Swans’ dog, Beatrice. We are immediately struck with the absurdity of the situation: We know that therapy is expensive, even ineffective. Therapy for dogs, then, would just be a waste of money and time. But no matter, here are the Swans, talking about every awkward moment of their private intimate lives with a therapist, while their precious Beatrice reclines in human fashion on her own couch, listlessly falling asleep despite their goading.

The Swans don’t necessarily need to take Beatrice to a therapist. Certainly the money being spent on her therapy sessions could be better used to buy toys or kibble. But this kind of reasoning would not work on yuppies such as the Swans. After all, these are people who consider themselves lucky to have “grown up on catalogs,” who spend their free time poring over J. Crew magazines and sifting through the newest additions to the L.L. Bean collection. The Swans are people whose romance began when their eyes met across the street from different Starbucks, who met for the first time while sipping soy lattes and working on their “Macs.” They are the discontented wealthy, the delusional consumers, the disconnected people who put their trust and faith in brand loyalties and seek happiness and comfort in expensive purchases. They revel in the joy of catalog shopping because “you don’t have to talk to anyone.” Even with each other, they communicate more in their conspicuous consumer choices than they do in actual conversation.

And as the film suggests, these are people who are tragically boring and unhappy. Their neutral-toned clothes, save for the occasional splash of “merlot,” suggest they have very in the way of personality. They lack excitement, and we can’t help but feel their sex lives are equally dull (as Meg says early on in the film, “[they] got a book, The Kama Sutra…” Only a haplessly out-of-love couple would need a book to teach them to love one another). Indeed, we see them as a nonsexual couple, and Beatrice as their surrogate child.

And as such, Beatrice falls subject to their crazed “stage parent” antics. The Swans’ manic behavior comes to a peak in the moments before Beatrice takes to the stage. Upon finding that Beatrice’s toy “Busy Bee” (a character almost in its own right) is missing during the ritualistic pre-show preparation, Meg storms off searching for a new one. “Raised on catalogs,” with apparently minimal experience or skill in face-to-face human interaction, Meg struggles to communicate with the store manager, only to give up and return with the “wrong” toy. Posey’s performance is particularly derisive, and exposes the absurdity of our consumer culture: such is the state of society that anything we could possibly want is available for us to buy. Even toys for our dogs are available in multiple varieties and colors, and still, it’s never enough, and we are never satisfied.

When Beatrice eventually buckles under the extreme pressure of the Swans’ ceaseless “freak-outs,” they discard her (perhaps put her down?) in favor of a new dog, Kipper, who they gush about at another one of their therapy sessions. Again, the Swans are depicted here as falsely believing they can control their lives with the things they buy. If the dog doesn’t work, get a new one. If the clothes don’t fit, get a new wardrobe. Fittingly, the Swans are shown in their epilogue wearing a rainbow of bright and pastel colors, reflecting their re-energized spirit and enthusiasm for their new pet.

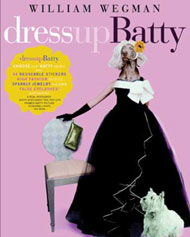

When Meg and Hamilton are frantically trimming Beatrice’s whiskers, brushing her coat, and giving her pep talks, like the other contestant couples around them, we see the human condition with all its follies on display. These are people who probably pay exorbitant fees to send their dogs to pet spas, who just might buy ridiculous outfits for their dogs so that they can more easily pretend they’re people.

The film is humorous and effectively satiric, because it reminds us that these are dogs, and that their misguided owners are human. Prolonged shots of the owners with their dogs show the dogs looking indifferent and unaware. As was probably the case in filming, so it is with dogs in shows: they may “sense the tension,” as the commentator suggets, but they are no more cognizant of the importance of the show to their owners than their owners are willing to acknowledge the dogs’ indifference.

The film reminds us that the contestants and their animals are participating in a dog show, a sadistic competition created by pet owners to take their extreme abuse of their canine companions to an obscene level. Dogs are animals, and naturally have no need for plush insect toys or trimmed whiskers. Yet who comes out looking more rabid, the humans or the dogs? In the end, the human characters are understood to be the irrational ones.

No comments:

Post a Comment